Losing grip – Return to rear geometry

Today I’ll continue my endeavour to explain rear geometry, an enterprise that is quite the challenger, but the effort luckily rewards me with one geometric discovery after the other. Ha! Hands up if you saw what I just did? Two missing, true, but since they are verbs rather than nouns, I consider myself excused. But I digress. It happens.

Well, as I was saying, today’s subject is rear geometry, once more. I’m dissecting it bit by bit, but don’t worry, I’ll sum it all up eventually. Last week was on the topic of parallell A-arms of equal length, and why that’s a bad thing. Because you get positive camber on the outer wheel in a turn, that’s why. With that matter settled, we’ll now look into how upper arm length affects camber when the chassis rolls, as it does in a turn.

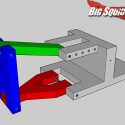

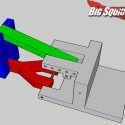

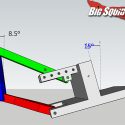

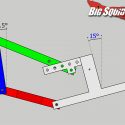

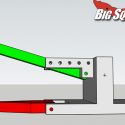

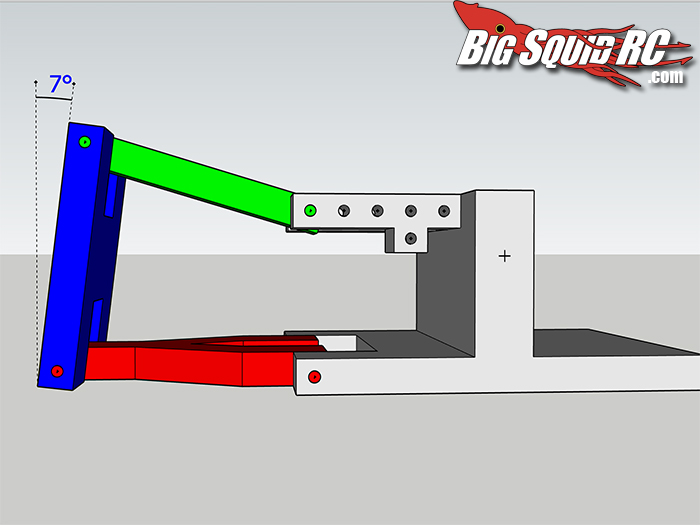

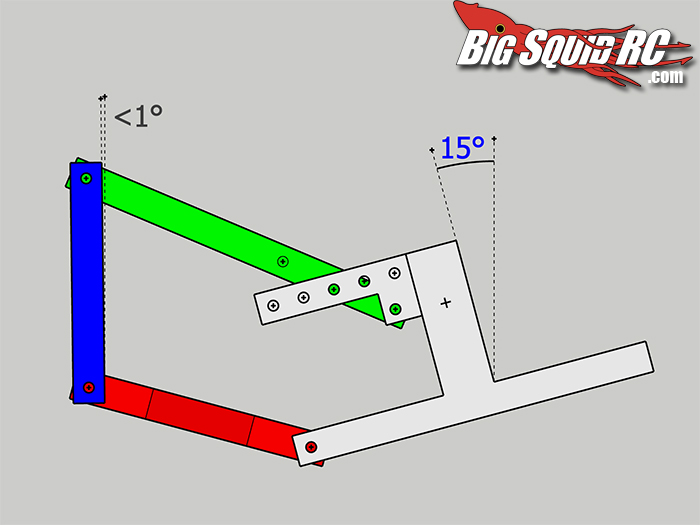

If you’re a regular reader, you know the drill. First, the basic setup, now with the upper link inclining towards the center of the car and a generous negative camber – after all, we’re drifters:

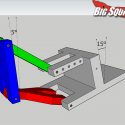

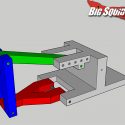

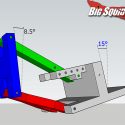

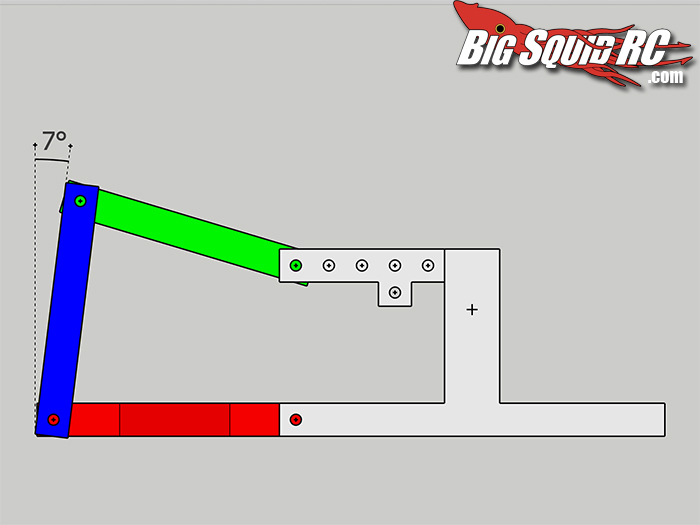

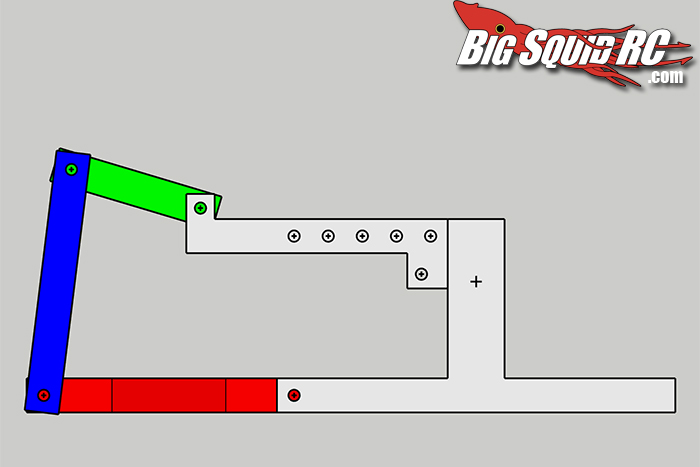

Now, let’s do a right turn and roll, from this:

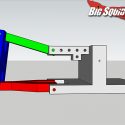

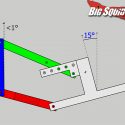

To this:

The chassis rolled an arbitrary 15 degrees, the knuckle (blue), a lot less. Way better than the parallell arms we had in the last column, but still moving in the direction of a positive camber. Depending on wheels, we might have a wider contact patch now. By the way, never mind the absolute numbers in the illustrations, just the relationship between them and how they change.

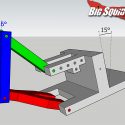

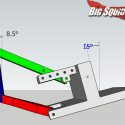

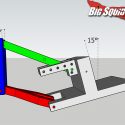

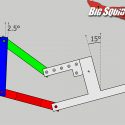

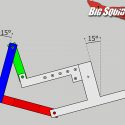

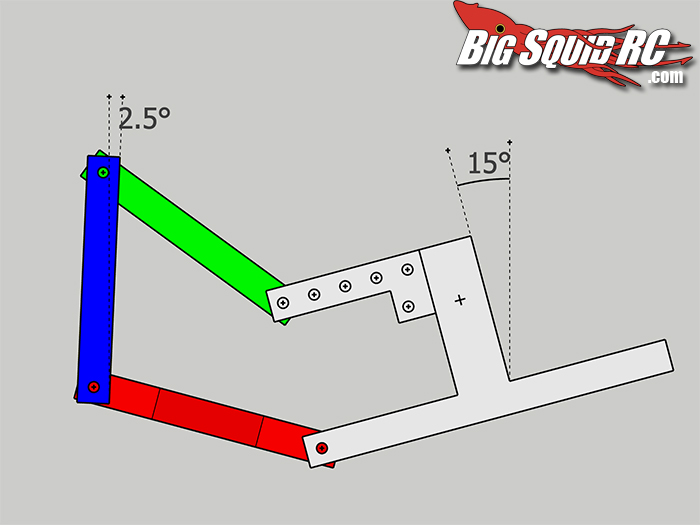

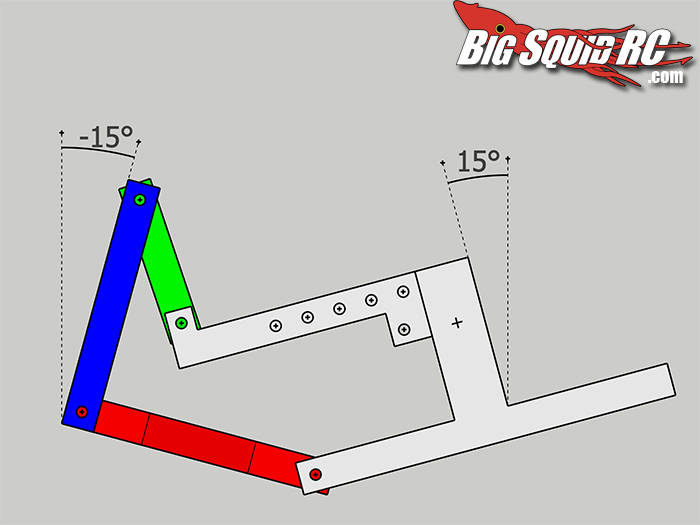

But what happens with a longer arm, set at the same angle? Like this:

Have you read my previous columns, you will have guessed it: we get an even bigger movement in the positive camber direction. In this particular setup, we actually get a positive camber, but only just.

Have you read my previous columns, you will have guessed it: we get an even bigger movement in the positive camber direction. In this particular setup, we actually get a positive camber, but only just.

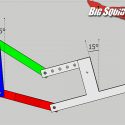

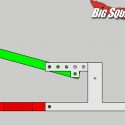

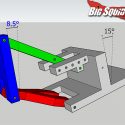

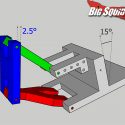

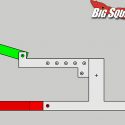

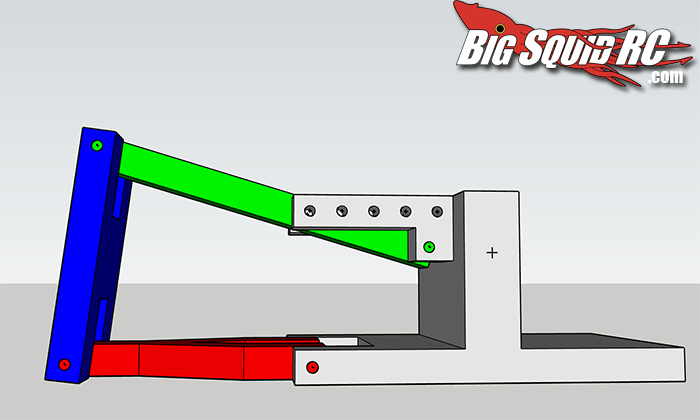

Naturally, if we do the opposite, with a shorter upper arm in the same angle, the opposite happens. Have a look at this setup:

Naturally, if we do the opposite, with a shorter upper arm in the same angle, the opposite happens. Have a look at this setup:

Ugly, I know, but it serves its purpose of illustrating basic car geometry. When we, again, turn right this happens:

Ugly, I know, but it serves its purpose of illustrating basic car geometry. When we, again, turn right this happens:

Lots of camber progression, going from a little negative, to very negative. Hence: shorter upper arm gives us increased negative camber in a roll. Just as it gives us more negative camber in squat, when accelerating.

Lots of camber progression, going from a little negative, to very negative. Hence: shorter upper arm gives us increased negative camber in a roll. Just as it gives us more negative camber in squat, when accelerating.

Actually, different opinions will be found on the internet on this issue, some saying that the upper arm length have opposite effects in squat and roll, respectively. I firmly believe this is wrong, and I have just shown why. In essence, the knuckle always follows a set trajectory – it doesn’t know whether the car rolls or squats, and in both cases the suspension (on the outer wheel in case of the roll) is compressed. Thus follows, that upper arm length has the same effect on camber progression in both accelaration and on the outer wheel when turning.

To summarize:

Shorter upper link: increased negative camber (more camber gain).

Longer upper arm: less camber gain, possible even going towards a positive camber.

And, for the sake of completeness, let’s repeat what we learned in this column:

More angle of the upper link (as in more inclination towards the center): increased negative camber in a squat or roll.

Less angle: less camber gain.

Now, what to do with this? Well, now you hopefully know what actually happens when you change the length of those upper links, and why it might be worth having a go at it. Should I not have made myself totally clear, never mind. Just turn those buckles one way or the other, and see what happens. Turn a lot, test drive, and then dial back. That way you get a clear appreciation of what direction you are going with your changes, and can then rein them in to the desired effect.

Finally: Columbia and Atlantis. Just saying.

Why don’t you click this link to read another column. There’s plenty of good ones to chose from.